Newsroom

Innovative Nanoparticles Enhance Immune Response Against Ovarian Cancer

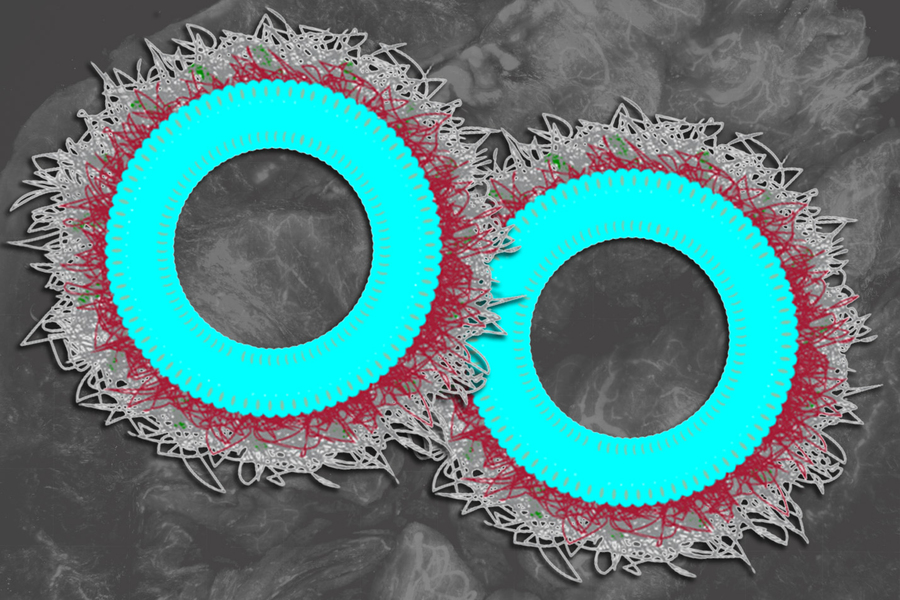

Cancer immunotherapy represents a groundbreaking approach that harnesses the body’s immune cells to combat tumors, proving effective for various cancer types. However, its efficacy is limited for certain tumors, particularly ovarian cancer. In response to this challenge, researchers at MIT have developed innovative nanoparticles designed to deliver an immune-boosting molecule known as IL-12 directly to ovarian tumors. When combined with immunotherapy agents called checkpoint inhibitors, IL-12 significantly enhances the immune system’s ability to target and destroy cancer cells. In preclinical studies involving a mouse model of ovarian cancer, this combination therapy successfully eradicated metastatic tumors in over 80% of the subjects. Remarkably, even after reintroducing cancer cells to simulate recurrence, the immune systems of these mice demonstrated a strong memory of the tumor proteins, effectively clearing them once again. “What’s truly exciting is our ability to deliver IL-12 precisely within the tumor environment. By designing this nanomaterial to carry IL-12 on the surfaces of cancer cells, we can essentially trick the cancer into activating immune cells against itself,” explains Paula Hammond, an Institute Professor at MIT and a key contributor to this research published in Nature Materials. The study’s findings highlight a significant hurdle that many tumors, including ovarian cancer, face: they often produce proteins that inhibit immune cell activity, creating an unfavorable microenvironment for immune responses. Although T cells are critical for eliminating tumor cells, they are often rendered ineffective due to interference from cancer cells. Checkpoint inhibitors aim to restore T cell function by removing these suppressive proteins. Yet, for ovarian tumors, this approach alone frequently fails to initiate a robust immune attack. “In ovarian cancer, there’s a lack of stimulation even after removing inhibitory signals. Simply put, no one is ‘hitting the gas,'” notes lead author Ivan Pires. IL-12 serves as a potential solution to boost T cell and other immune cell activity. However, administering high doses of IL-12 can lead to significant side effects, such as flu-like symptoms and severe complications including liver toxicity and cytokine release syndrome. Previous work from Hammond’s lab introduced nanoparticles capable of delivering IL-12 directly to tumor cells, which mitigated side effects associated with conventional injections. However, earlier versions of these particles released their therapeutic payload too rapidly, limiting their effectiveness. In the latest research, the team has refined these nanoparticles to allow a gradual release of IL-12 over approximately one week by employing a new chemical linker that enhances stability. “With our advanced technology, we have optimized the chemical properties for controlled release, leading to improved efficacy,” says Pires. These nanoparticles comprise tiny lipid droplets known as liposomes with IL-12 molecules securely attached to their surfaces using a stable linker called maleimide. Additionally, the researchers coat these particles with poly-L-glutamate (PLE), enabling targeted delivery to ovarian tumor cells. Upon reaching the tumors, the particles adhere to cancer cell surfaces and slowly release IL-12 while activating nearby T cells. In experimental trials involving mice with metastatic tumors located in various organs, the nanoparticles effectively engaged T cells to attack cancerous growths. When tested independently, the IL-12 nanoparticles eliminated tumors in about 30% of the mice and significantly increased T cell accumulation in tumor areas. Further testing combined these nanoparticles with checkpoint inhibitors, resulting in over 80% tumor-free outcomes, even in challenging ovarian cancer models resistant to standard immunotherapies or chemotherapy treatments. Typically, ovarian cancer treatment involves surgery followed by chemotherapy; however, residual cancer cells can lead to new tumor growth. Establishing an immune memory of tumor proteins could be crucial in preventing such recurrences. In this study, when researchers injected tumor cells into the previously cured mice five months post-treatment, the immune system recognized and eliminated the new cells. “We observed that the cancer cells did not re-emerge in those mice, indicating that we successfully established immune memory,” states Pires. The research team is currently collaborating with MIT’s Deshpande Center for Technological Innovation to develop this nanoparticle technology further into a viable commercial product. Earlier this year, Hammond’s lab reported a novel manufacturing method that could facilitate large-scale production of these advanced nanoparticles. This research received funding from various institutions including the National Institutes of Health and the Koch Institute Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute.