Newsroom

Innovative Metalloenzyme Research Bridging Science and Art for Enhanced Reactivity

As the stunning landscapes of California’s Napa Valley pass by, a young boy named David Kastner engages in a lively discussion with his father. Their conversation effortlessly transitions from the principles of gravity to the intricacies of electromagnetism. From an early age, David’s curiosity about science has been a constant companion during these drives.

Unlocking Enzyme Mysteries with Computational Science

“I’ve always been intrigued by the complexity of the universe and the limited understanding we have of it,” reflects Kastner, now pursuing his PhD in biological engineering at MIT. “My passion lies in uncovering new truths about our world.” Fast forward nearly two decades, Kastner is delving into the fascinating realm of metalloenzymes under the guidance of esteemed professors in chemical and biological engineering. His research is driven by an aspiration to unlock the chemical and medical potential of enzymes using innovative computational and mechanistic techniques.

Kastner’s work aims to elucidate the fundamental blueprints that dictate enzyme reactivity through advanced computational methods. His approach intertwines physics, chemistry, biology, and even art—an integral aspect of his life since childhood. By creating stunning 3D visualizations of molecular systems, he makes complex scientific concepts accessible to a broader audience.

The Quantum Lens on Nature’s Catalysts

Balancing aesthetics with functionality, Kastner’s research spans various domains including quantum chemistry, protein engineering, and synthetic organic chemistry. After earning his degree in biophysics from Brigham Young University, he honed in on metalloenzymes during his PhD studies at MIT.

Focusing on high-valent metalloenzymes—enzymes that contain highly reactive metal atoms—Kastner is particularly fascinated by non-heme iron enzymes. These enzymes not only exhibit a wide range of chemical reactions but also have direct implications for human health, along with the versatility needed for engineering novel reactivities.

However, modifying existing enzymes to exhibit new reactivities presents significant challenges. In his first published study, co-authored with colleagues from the Kulik Research Group, Kastner highlighted these complexities.

His research investigates the mechanistic differences between two types of high-valent enzymes: non-heme iron halogenases and hydroxylases, which are capable of activating typically inert C–H bonds. By analyzing structural databases and conducting molecular dynamics simulations, he uncovered key interactions that subtly affect substrate positioning angles and consequently influence reactivity. His computational insights offer new avenues for converting halogenases into hydroxylases and vice versa.

“Unlocking the secrets behind nature’s most efficient catalysts necessitates meticulous observations at the quantum level.”

While understanding an enzyme’s structure is vital, sometimes deeper analysis is required. “Introducing a metal into an enzyme’s core complicates modeling significantly,” he notes. “Unique and advanced tools are essential to grasp reactivity, which is why quantum chemistry calculations are crucial for our research.” Unlocking the secrets behind nature’s most efficient catalysts necessitates meticulous observations at the quantum level. The reactivity of an enzyme is dictated by the interplay of its electrons, which justifies the reliance on cutting-edge quantum computing methods.

The importance of viewing enzymes through a quantum mechanical lens became evident in Kastner’s latest publication. Together with collaborators, he revealed that the reactivity of certain miniature artificial metalloenzymes is governed by dynamic charge distributions—an insight that illustrates how electron fluctuations can influence an enzyme’s structure.

Bridging Art and Science for Broader Impact

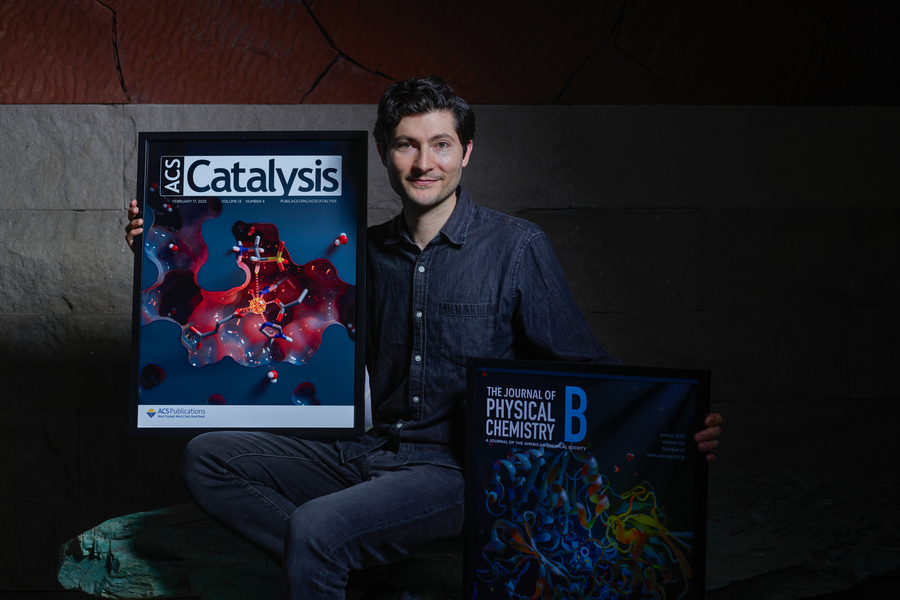

Kastner’s dual passion for art and science is evident in his use of 3D graphics programs like Blender and VMD to visualize macromolecular interactions. His artistic endeavors have graced the covers of prominent scientific journals published by Nature and the American Chemical Society. However, his artistic journey began with simpler drawings during childhood.

“I loved to draw everything,” he recalls. “It was my favorite pastime, and I would often ask others to draw alongside me.” Inspired by his mother’s hyperrealistic nature art, Kastner took traditional art seriously during high school, winning numerous competitions with his charcoal and oil paintings. Yet he struggled to see how these skills could merge with his academic interests.

“At that point, I hadn’t realized how to bridge my passion for art with my love for science,” he admits. “They felt like separate worlds—something I rarely encountered in conversations with others.”

Had he lived during the Renaissance period, this divide may not have existed. The era was marked by individuals who blurred the lines between disciplines—none more so than Kastner’s favorite scientist: Leonardo da Vinci.

“It’s remarkable that the same person credited as the father of modern anatomy also painted the ‘Mona Lisa,'” he observes. “The world would benefit from more individuals like da Vinci who harmonize science and art.”

Kastner believes that fostering such connections could help restore public trust in scientists. Scientific literature can often be dense and technical, making it difficult for the average person to grasp complex experiments and results. This is where art can play a pivotal role.

“If we communicate our scientific findings in ways that resonate with everyday people, we could alleviate some skepticism towards science,” he suggests. “While traditional peer-reviewed papers are necessary for reproducibility, scientific art can transform complex data into relatable visuals, inviting people from all backgrounds to engage with science through a universally understood language.”